High-Maintenance, In-Between: MoMu Antwerp’s Girls

Words by Molly Apple

Momu Antwerp has been a creative safe haven for me since my first visit earlier this year. This exhibition, Girls, was especially anticipated—not only because I am a girl, but because I have often been labeled a “high-maintenance” one, much to both my defiance and bemusement. The show poses elemental questions that greet every visitor: How has girlhood been represented? How is it remembered? And how does the idea of “the girl” continue to shape visual culture and fashion?

These questions rippled through my mind alongside my recent first-hand experience of Jenny Fax’s Paris Fashion Week ‘girl-office-core’ presentation and a TikTok forecasting lace as a top 2026 trend that I had watched on the train to Antwerp from Paris, prompting countless musings even before I stepped into the exhibition. I visited just before Belgian designers Julie Kegels, Florentina Leitner, and Und Uli unveiled their co-created gifts at the Momu Shop on November 7, 2025, an evening buzzing with local insiders and enthusiasts.

Edgard Tytgat De laatste pop, 1923

The term ‘girl’ has historically been rejected by many Second-Wave feminists, who argued it infantilizes women. Today, however, younger feminists are embracing youthful femininity, a perspective clearly reflected in this momentous exhibition curated by Elisa De Wyngaert. She brings together a range of tactile references, from Simone Rocha’s ballerina-core to Molly Goddard’s voluminous pastels and kitschy vinyl knick-knack Ashley Williams outfits, creating a contemporary dialogue with nostalgia, identity, and playfulness.

Walking into the show, I encountered historical garments such as Victorian children’s cotton nighties, reminiscent of the sheer, delicate styles now reimagined by some “trad-wife” influencers. Anything milky and sheer enough to require handwashing and careful hanging. These clothes, seemingly innocent, carry the labor of care and the weight of perception. So much about girlhood, and womanhood, is about being perceived, and the judgments we place on women who dare to project their chosen narratives. The internet loves Nara Smith rage-bait, and I couldn’t help but wonder how she’d feel walking through the expo with her little girls. These perceptions—being seen, judged, and scrutinized—are a reality only amplified by social media culture. De Wyngaert notes, “Today, being a teenager often means balancing two identities: how you present yourself in real life and how you perform online.’ The work captures the complex tensions young women navigate: the constant push and pull between irritation and desire, hatred and admiration.”

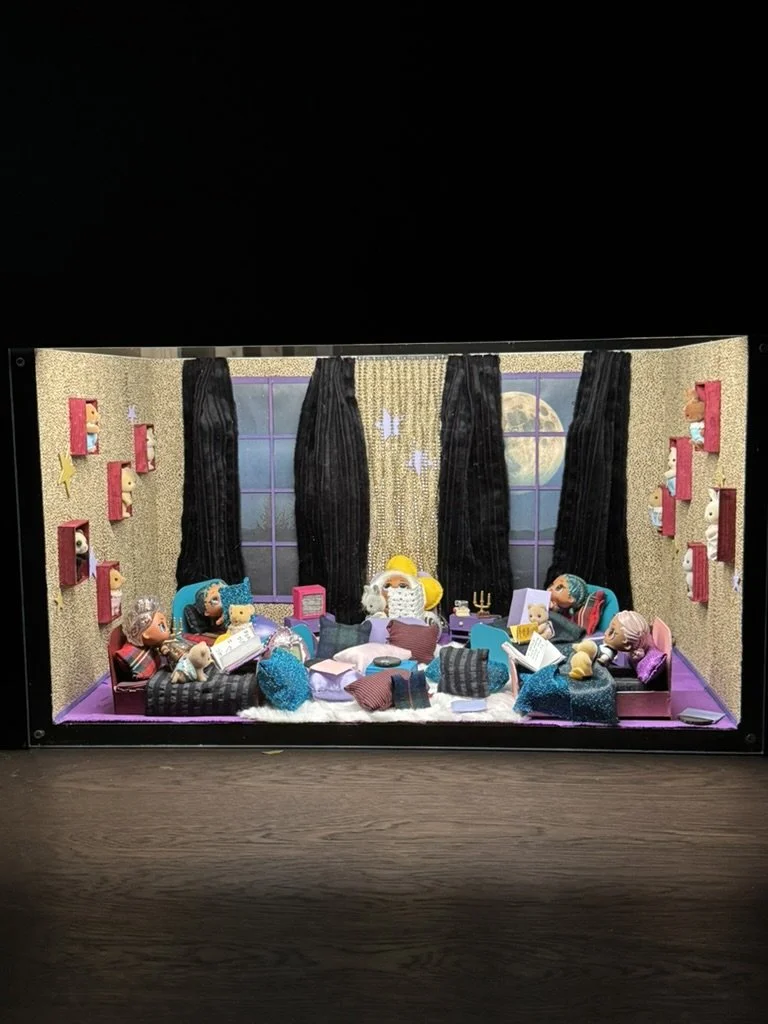

As I rounded the corner, I considered a scary thought: whether Nara Smith is too young to know that Sofia Coppola’s Virgin Suicides was based on the book by Jeffrey Eugenides. The cult film’s bedroom setup was recreated inside the exhibition and reflected across many TikTok and Instagram feeds of museum visitors, highlighting the cultural obsession with teenage melancholy. There are two more bedroom installations as you walk through: one by designer Jenny Fax, reflecting the secret rituals of OCD behaviors she shamefully kept hidden in her childhood bedroom, and one by Chopova Lowena, who revisits the chaos and creativity of coming of age while sharing a bedroom with siblings and breaking the rules—completely closing the circle in my head behind her punk-girlhood aesthetic brand. Together, these spaces explore rebellion, ritual, and the intimate interiority of growing up.

Chopova Lowena Bedroom Installation

Jenny Fax Bedroom Installation

Virgin Suicides Bedroom Installation

It’s interesting that the two themes of boredom and rebellion go hand in hand at such a volatile point of growth in youth. Every girl can relate to the feeling of laying on the bed, feet dangling off, plotting world domination. “‘As teenagers… the feeling of being strange or ‘othered’ can render girlhood a period one longs to rebel against—or escape altogether.’”

The derogatory label ‘Jewish American Princess’ stuck to me, like the ugly slur that it is, since my teenage years—maybe because I enjoy fashion and the frivolous things in life externally, but also because the world loves to minimize a woman’s passions by squishing her ego and making her build shame around appearance and presentation. Girls often look to one another for cues—what’s “in,” what’s “out”—so I asked Elisa how the exhibition engages with the idea of girls spectating each other, or being spectators themselves (via mirrors, selfies, social media, peers). How did you choose to put the first artist with the TikToks on repeat as the first piece as you enter the exhibition? She notes, “In the exhibition, as you noticed, we show the work of artist Maya Man, who examines internet culture and the performance of self and femininity on platforms like TikTok. Her piece Love/hate confronts public perceptions of young women online, featuring a video of clips from her own profile displayed on an iPhone attached to a pink, ribboned boxing ball. I wanted to open (or rather end) with this very digital experience of girlhood. In art history, the ‘young girl’ was often an anonymous muse: a daughter of, a silent subject playing the piano, holding a kitten, surrounded by symbols that alluded to her virtue and innocence. Today, girls online have claimed visibility as both creators and spectators, shaping culture rather than simply embodying it.”

There were many works beyond clothing and accessories that Elisa curated to confront notions of girlhood and boredom, one of which is Jas Knight’s 2023 painting Croquis for Fugue 14, featuring a young girl in traditional girls’ dress capturing a celebratory scene on her smartphone in his hyperrealistic style referencing Dutch genre painting. It captures present-day anxieties around technology’s pervasiveness among the young and the ironic reality that technology may actually pervade boredom rather than “solve” it. Another favorite painting in the expo was Nathanaëlle Herbelin’s 2023 Charlotte, her neighbor painted in a moment of “intimate gender expression.” I wonder: is any expression of gender not intimate? Whether you’re uncertain, undecided, or totally confident in your gender expression, it’s still an extremely exposed position, both to build or let down boundaries. The exhibition expertly reflects the “courage of becoming.”

There are definitely little Easter eggs among the expo that brought a surprising smile to my face and broke up some of the more dense thoughts and reactions to thought-provoking works, such as mini Calico Critter dollhouse cutouts at viewers’ feet, not to mention Monchichi dolls making friendship bracelets. I was delighted to let out a giggle when seeing a plush toy dog handbag, one not unlike a “Made in China” version I had recently purchased for my three-year-old niece from TJMaxx, placed below a gown dated 1936. “Much like women’s fashion, which often engaged with codes of girlhood, the earliest children’s clothing likewise reflected adult styles in miniature.”

Puppy Handbag with Zipper ‘much like women’s fashion, which often engaged with codes of girlhood, the earliest children’s clothing likewise reflected adult stylist in miniature. The child’s handbag fashioned in the form of a plush dog toy.’

Nigel Shafran. Teenage Precinct Shoppers, East London. 1990.

I switched from public to private schools around age 10, where I shifted from perceived “middle class” to “lower class” externally. I immediately surveyed my cohorts, taking in their cable knits. Just a year before, I’d begged my mom for high-heel flip flops from Target that my bestie Mercedes flaunted on the playground. Now I was dragging her to Nordstrom Rack to browse the discount Polo Ralph Lauren section. Don’t worry, I wouldn’t dare pop my collar—that was too WASPy, even for a girl yearning to fit in. It took me a solid three years in prep private school before I rejected the status quo and sunk back into my core rebellious nature. I asked Elisa to what extent she thinks consumerism—brands, trends, micro-brands, social media aesthetics—mediates these relationships (trying to look like your peer group or stand out from it), to which she answered: “When it came to girls/teens and consumerism, I mostly wanted to take away the judgment that surrounds teenagers’ focus on shopping. We display work from Nigel Shafran’s series Teenage Precinct Shoppers. This series was shot around a shopping centre in suburban East London and originally appeared in i-D magazine in 1990. To adolescents, shopping is both a symbolic and an economic rite of passage. In a world where teenagers can rarely simply be together without being seen as a nuisance, the shopping street has long provided an important ‘third place’ to explore newfound independence without parental supervision.”

Elisa references Eimear Lynch’s Girls’ Night beautifully in the exhibition’s publication. Fitting in can sometimes be just as empowering as standing out—here is strength in collectivity. Walking the fine line between the two is something every girl, and woman, attempts throughout her life.

This in-between tweenhood was artistically represented in the exhibition through designers that Elisa carefully curated. She notes: “Among the designers featured, there is a similar respect for both the meaning and layers of girlhood and womanhood and their customers. The intensity of our teenage years continues to inspire fashion designers to revisit their own memories, drawing on them to reimagine the clothes they once wore, obsessed over, or dreamed of. In the 2010s and 2020s, a new generation of designers has been crafting deeply personal visions of early womanhood. Some draw inspiration from girlhood’s silhouettes, the comfort of baggy shapes recalling childhood clothing, while others rework hyper-girlish symbols. The work of these designers, most of whom are women, disrupts and redefines traditional femininity, moving toward a girl’s gaze that is accessible to all ages and genders.”

Becoming content is a mode of expression I wish to attain, becoming a girl entering her 30s. Edgard Tytgat’s 1923 painting De laatste pop particularly resonates with my current state of mind. It features a girl on a chair, her doll sitting below her. The painter notes he was often deemed a “naive painter,” his vision “that of a child,” which he later came to accept as a compliment. I too often feel that looking too young may hold me back professionally due to being perceived as inexperienced—a blessing and a curse. Doll-faced girls, much like real dolls, once treasured and coddled as children, are left behind and hidden when they become adults and no one takes them seriously. I was even told by my therapist recently that she faced the same issues in her late-twenties and early-thirties, so she started wearing fake prescription glasses and her peers began taking her more seriously. I’m definitely adopting her theory, but need to find the right pair that will aesthetically elevate both my look, and my age. Comedian Esther Povitsky frequently incorporates her youthful appearance into her stand-up comedy, often juxtaposing it with more mature or raunchy topics for comedic effect. As someone who relates to comedy as a coping mechanism, I’m more satisfied with accepting criticism as a compliment and twisting the narrative to my benefit. It’s a double standard: once women grow crow’s feet, they become invisible altogether.

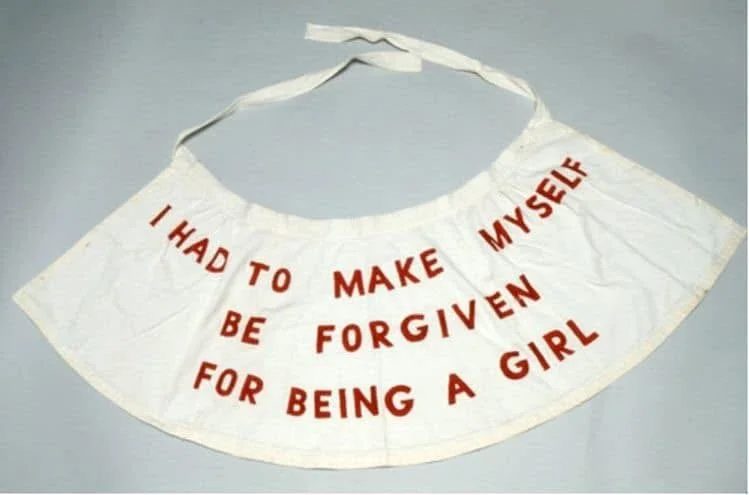

Louise Bourgeois Garment from the performance She Lost it, 1992

The sartorial category of the “teenager” only emerged in the 1950s, as housewives began to dominate consumer culture. Traditional motifs such as Peter Pan collars were born, and so was shame. I was immediately drawn to an apron under a glass display case featuring the red lettering: “I had to make myself be forgiven for being a girl,” made and worn by artist Louise Bourgeois for her 1992 performance piece She Lost It. I felt a kindred spirit in Louise, also the second daughter in her family. While I didn’t face gender disappointment as she did being born in 1911, I did feel an intense pressure to utilize the power that feminism had given my generation: “girls can do anything,” so I must “do everything,” which often resulted in burnout and dissatisfaction despite accomplishments. There’s such a vast generational timeline of female artists in the exhibition, and I was curious about feedback Elisa had received from multi-generational families visiting together. She notes: “It felt important that the exhibition foster an intergenerational dialogue and a recognition that our generations and experiences are, in many ways, not so different. It was crucial that the project be inclusive of LGBTQIA+ youth and developed in dialogue with today’s teenagers. In 2024 and 2025, we organized several focus groups with ‘girls’ aged 9 to 19. The insights from these sessions shaped key themes in the exhibition (such as exploring the inner worlds of teens through sleep, boredom, and rebellion) and served as a starting point for the video installation by director Leonardo Van Dijl, in which he interviews girls and women between the ages of 9 and 80.”

Louise Bourgeois often said that her childhood never lost its magic, mystery, or drama. We display one of Bourgeois’s earliest diaries, revealing an intelligent young girl with a restless mind, attuned to social tensions and her own shifting emotions. On these pages, she articulates the intensity of her feelings and how likely they would be dismissed by adults—a sentiment that resonates across generations of adolescents.

Some experiences may be specific to today’s teenagers, such as navigating online identities, but many of the emotions tied to coming of age remain universal. It is crucial that we truly listen to what teenagers have to say and remember who we once were as teens. Mostly, it’s joyful to explore together how and why we see things differently—it opens conversations. Elisa notes further: “Much of the work in the exhibition wants to articulate that girlhood isn’t something we leave behind, but a perspective that continues to shape how we look at the world. That’s why those years are so precious. Much of the feedback so far has been that both young people and older audiences felt seen or touched by the art and stories, which is wonderful to hear.”

If women are the ones feeding capitalism due to the 1950s rewiring of consumerist habits, then why are women labeled “high-maintenance” for choosing to express themselves creatively through clothing nails, hair, or makeup?

In her song Matcha Cherry, Princess Nokia sings:

“Lemon girl, kiss, kiss, she's so sorbet

Lip gloss, glass skin, and a doll-like face

Bows tied, mini skirt, skirt, skirt, ballet

Iced chai, stardew, internet cafe

Hello Kitty on my gun, but I pressed the safe

I'm a Pinterest girl with a stripper name

Brow tint, lash lift, nails done, life's great

Brow tint, lash lift, nails done, life's great”

These lyrics played in my head as I viewed the accessories on display, such as the recent D’heygere x Nails by Mei AW 2025 Kawaii Stiletto Nail Earrings, Ashley Williams SS25 wig with flowery combs, Maison Martin Margiela Baby Doll Hand necklace (SS 1999), and Silver Sparkly Princess Wand (AW 2001). Even the most internet-viral Conner Ives Protect the Dolls t-shirt was procured for the expo, furthering the narrative that girlhood extends beyond chromosomal definitions and is, instead, a state of mind. All behind museum glass, the girl in me wishing I could reach out and play with the objects

These designers have flipped the narrative by weaponizing femininity as strength rather than weakness, as Princess Nokia does with her latest album cover featuring her period blood on display. I’d like to think Elisa would have chosen to display her ‘GIRLS’ cover photo for the expo had the album dropped before the curation closed. I did have the chance to ask about her photography curation, as I wondered: how much did you consider the angle of “production” (girls producing and consuming their own visual meaning) versus “being consumed / looked at”? Elisa notes:

“I wanted to include photographers from different generations who have shaped how girlhood is portrayed. Figures such as Lauren Greenfield, Nigel Shafran, Roni Horn, Micaiah Carter, Nancy Honey, Leticia Valverdes, Eimear Lynch, and Petra Collins were on my list from the outset. Each has brought a nuanced and distinctive vision of girlhood into books, exhibitions, and digital culture. Their work never treats girls as objects but instead approaches them with respect, often co-created or guided by the teenagers’ own boundaries and agency. That same sense of comfort and trust is captured in This is Me, This is You (1997–2000) by Roni Horn.”

I felt this reflected perfectly in the controversial images of Dakota Fanning when she was only 12 years old, photographed by Juergen Teller for the Marc Jacobs SS 2007 campaign shot in Los Angeles in 2006. There’s a larger conversation to be had about advertising featuring children, but that could fill an entire article—or be further explored in the much-recommended book Fashionable Childhood: Children in Advertising by Annamari Vänskä.

As a Creative Director of a magazine newly exploring motion pictures, I lingered especially long in the room projecting clips of girls and women expressing themselves femininely on the big screen. Returning to the projection space after completing the exhibition, I wondered how I could channel all the bricolage memories of my girlhood—jollies and follies alike—into an expressive piece that flips the narrative of boredom into engagement, rebellion into submission, and the in-between into being on top. Stay tuned for a Submissively Engaging film about a Woman on Top.